Editorial

|

|

|

Having crossed the river,

where will you go,

O friend ?

There's no road to tread,

No traveler ahead,

Neither a beginning,

nor an end.

Kabir

A lab is born.

After a few years of uncertainty, rumors, steps forward, steps backward, the Centre for Himalayan Studies (CNRS–CEH. UPR 299) and the Centre for South Asian Studies (CNRS/EHESS–CEIAS, UMR 8564 ) have merged. We are happy to announce the birth of a major newcomer, under the auspices of the CNRS and the EHESS, on the social sciences world map: the Centre for South Asian and Himalayan Studies (CESAH).

Where are we heading?

Including more than fifty permanent researchers, associate members, doctoral students and a strong support team, the CESAH is (almost) up and running. From misgivings to total unity, the path has been paved with questions about our not-to-be-forgotten legacy, and our future, which has yet to take form. Former colleagues become formal colleagues. New habits, new ways of functioning, a new logo: newness rhymes with prowess. The prowess of combining history, geography, sociology, political science, literary studies, anthropology to strive toward producing knowledge on our extended region. The prowess of uniting when our research covers regions that span from Sindh to Yunnan, from Tibet to Bangladesh, even including the diasporas as colonial heritages.

Thanks to new research axes, the CESAH is more than ever committed to developing original approaches to social and cultural dynamics in a region that houses more than a fifth of humanity. The stakes are high and we’re determined to live up to them. The research team is now the largest of its kind in France (and in the world) with a vested interest in South Asia and the Himalayas and their diasporas. A huge responsibility lies on our shoulders.

Having crossed the rubicon of the merger, we’re now back to the long quiet river of producing knowledge, all together. The CESAH will have many offshoots, which you will read about in this the first issue of the CESAH newsletter.

The conversation between past and present directorships gives an insight into the inner process of the merger.

Anne Castaing, Tristan Bruslé, Francie Crebs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONFERENCE IN HONOR OF JACQUES POUCHEPADASS (1942-2021)

|

|

19th september 2023

Amphithéâtre 150, Centre des Colloques, Campus Condorcet

A historian who specialized on contemporary India, Jacques Pouchepadass has left his mark on South Asian studies in two ways. This conference will go back over his whole career as a researcher and teacher in order to show how important his work has been in areas like rural studies and environmental studies on the one hand, and the historiography of Subaltern and Postcolonial Studies on the other. The presentations will also underscore the ways in which he inspired specialists working in other fields and regions, well beyond the limits of Indian studies alone.

|

|

|

YOGA AND MUSLIM SOCIETIES: TRANSREGIONAL PERSPECTIVES

|

|

8th and 9th november 2023

Venue: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales/ School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, Centre de la Vieille Charité, salle du Miroir – salle A, 2 rue de la Charité13002 Marseille.

While the practice of yoga and the production of texts and discourses on yoga in non-Hindu environments have been chiefly regarded as recent phenomena that spread from Western countries during 20th century and have now become a globalized trend, their roots go back to the premodern past. This conference aims to reconsider this issue by looking at the long-lasting interaction of Yoga and yogins with Muslim societies in a transregional perspective. The production of knowledge about yoga in Muslim environment is a multi-layered phenomenon that last over a millennium and includes multiple views and perspectives on yogins’ learning. From the Medieval period onward, an extensive number of texts dealing with Yoga and yogins - whether directly or obliquely - was written in Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and other languages of the Muslim world. After al-Biruni’s (d. ca. 1050) Arabic translation of Patañjali’s Yogasūtra, many Persian texts dealing with Yoga and yogins are produced in South Asia until the 19th century for different groups of readers. These texts circulated also outside South Asia and some Sufis of the Ottoman world practiced methods drawn from them. In South Asia, the existence of Muslim sects of yogis was a rather widespread phenomenon until the colonial period. While these groups have been progressively marginalized in post-colonial South Asia, during the 20th century the practice of yoga has increased in other regions of the Muslim world and nowadays thousands of people and especially women practice Yoga in Muslim countries, from Turkey to Indonesia including Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Contacts: Fabrizio Speziale (fabrizio.speziale@ehess.fr), Andrea Acri (andrea.acri@ephe.psl.eu).

For more information →

|

|

|

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE “Connected Histories of Dance IV”

|

|

Friday, November 17, 2023

20 Av. George Sand, 93210 St. Denis (The auditorium has handicap access) 1st floor (Metro line 12, ‘Front Populaire’ station)

Maison des Sciences de l’Homme-Paris Nord Auditorium

Circulation of artists, techniques and choreographic scripts between India, Europe and the Americas: the humanist creative work and pedagogy of Jean Cébron (1927–2019)

Organisers: Tiziana LEUCCI (CNRS, CESAH, LAP, Paris-Aubervilliers, Conservatoire ‘Gabriel Fauré’ Les Lilas Est-Ensemble, Accademia Nazionale di Danza, Rome), Marie FOURCADE (EHESS, CESAH, Paris-Aubervilliers) et Pierre PHILIPPE-MEDEN (RiRRa21, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3)

|

|

|

CESAH INTERNATIONAL ANNUAL CONFERENCE

“The Power of Images. The Images of Power”

|

|

December 12th and 13th, 2023

Campus Condorcet Centre de colloques Auditorium 1-22

Place du Front populaire, 93322 Aubervilliers

(Métro Ligne 12, arrêt : ‘Front Populaire’)

Organization: Tiziana LEUCCI (CNRS, CEASAH, LAP, Paris-Aubervilliers) and Marek ANHEE (EHESS, CESAH, Paris-Aubervilliers)

|

|

|

|

|

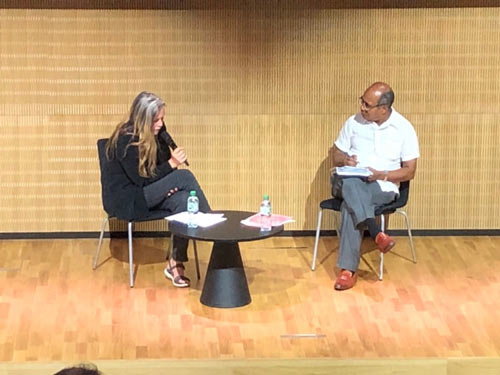

Conversation with

|

|

CESAH Past, Present

and Future

During the month of May, Michel Boivin (MB), former co-director of the CEIAS, Nicolas Sihlé (NS), former director of the CEH, and Anne Castaing (AC), current co-director of the CESAH, collaborated to answer a few questions Francie Crebs proposed on the past, present and future of the new lab.

|

|

FC: Can you say a bit about similarities and/or differences between the histories of the CEH and CEIAS before the merger?

AC: As the new co-director of the CESAH, what I’d like to see is the beautiful convergence of our two teams! Obviously, it’s our similarities that led to this merger and not our differences—which have to do with team cultures and not scientific issues. Of course, this “team culture” is linked with the size of both teams, which led to different modes of organization and administration, in other words different ideas of what a “team” can (and must) be. But Nicolas and Michel probably have more to say on this matter.

MB: I would add that, as both labs had an areal focus, relating to contiguous geographical areas, the merger was quite logical. As far as our differences are concerned, I would say that they have more to do with our histories, which are obviously different, and also with the orientations of the disciplines. But what is certain is that if there were differences, they were not an obstacle to a merger. The CESAH is proof of this!

“Obviously, it’s our similarities that led to this merger”

MB: NS: One difference in institutional history lies in the fact that the CEIAS was a UMR (unité mixte de recherche), a research unit placed under the dual umbrella of both the CNRS and EHESS, while the CEH was a UPR (unité propre de recherche), under the CNRS only. This means that the CEIAS was more closely involved with a degree-granting institution (the EHESS) than the CEH—although numerous CEH researchers have been involved in teaching at various higher-education institutions in the greater Paris area.

As Anne points out, size differences (with the CEIAS having more than twice researchers than the CEH) had important implications. These were not only organizational/administrative in nature: the relatively modest size of the CEH made it probably somewhat more feasible to devise scientific projects that could involve the entire unit.

FC: What do you have to say about collaboration between the CEH and the CEIAS before the merger?

AC: Of course there was a lot! But what is interesting today (and what we really must pay attention to) is precisely the “grey zones” of this merger: the new disciplines, the new geographical areas, the new paradigm that “appeared” for the respective teams. What, for example, can linguistics bring to the ex-CEIAS, and what can literature, history, gender studies bring to the ex-CEH? How can we re-think the new borders of our cultural area? All these issues are extremely exciting for us.

MB: Indeed, for the reasons mentioned above, multiple collaborative projects existed, and still exist. They were probably more at the level of individuals, but for example, CEH researchers were associate members of the CEIAS and vice-versa, as the fields of certain CEIAS members, such as Marc Gaborieau or Blandine Ripert, overlapped with the CEH’s area of specialization.

NS: These collaborations were indeed numerous, and fruitful. For example, on a personal note, I was always very grateful to see Véronique Bouillier, a CEIAS specialist of contemporary Hindu tantric traditions, participate in workshops that I co-organized on the anthropology of (tantric and other forms of) Buddhism. Comparative contrasts have always been good to think with.

FC: How did the idea of the merger come about?

“the CESAH is not only a result but also a process”

MB: Let’s say that the question should be asked of the INSHS (Institut des sciences humaines et sociales—Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences), who pushed the idea of the merger! Having said that, as I have already pointed out, the merger of the CEIAS and CEH was quite relevant from a scientific point of view.

FC: Were there any “growing pains” during the merger process and/or once it became official?

MB: No, I don’t think so, not particularly. On the other hand, one might note that certain questions were asked, since each center had its own traditions, regarding functioning, scientific policy, or, in cruder terms, about the budgetary choices they made. But in order to anticipate possible “growing pains,” many meetings were held. And above all, the organization of a retreat in Roscoff allowed us to “get everything out into the open.”

NS: Let’s say that the painfulness of the merging process was perhaps more pronounced in the experience of the numerically minority party, the CEH. For instance, the merger implied that this internationally well-known research unit focusing on the Himalayas was to become a mere numerically minor component of a larger research unit having South Asia as its center of gravity—a significant loss of institutional visibility. During the process, it seemed at times that this and other very real issues encountered by the CEH members were not very visible or meaningful to the majority party, the CEIAS, or at least to many of its members, but this is probably just a quite general sociological phenomenon.

AC: Interesting answers! I’d add that growing pains are still there, as the CESAH is not only a result but also a process. But yes, let’s remember that pains have to come with the fact of growing.

FC: Did everything go as planned with the merger process or were there things you had not anticipated?

MB: It's a bit difficult to give a precise answer, since, personally at least, I must admit that I have no other experience in this field of merging CNRS centers. As I said above, a lot of work was done upstream, in particular during the Roscoff retreat.

“The new center has enormous research potential, and I have no doubt that it will soon be one of the most important internationally”

NS: The process did take one or two years more than initially planned. This was due in large part to the absence of a full-time financial assistant position that was sorely needed for the merger project to appear sound and reasonable.

AC: Here also, I would not use the past tense. We are still merging and we still cannot anticipate everything. But I’d also like to reinvest the metaphor used by Francie: we’re growing together, and this process is full of unforeseen twists and turns that we have to experience and deal with together.

FC: How do you see the future of the new center? Are there synergies to be taken advantage of? Obstacles to be overcome?

MB: I am absolutely convinced that after a running-in period, the merger will strengthen research in the field of South Asian and Himalayan studies. A major step has already been taken with the work carried out by the members on the identification of research areas that allow everyone to be involved. The new center, the CESAH, has enormous research potential, and I have no doubt that it will soon be one of the most important internationally.

NS: I agree wholeheartedly that the perspective of interacting with a larger set of close colleagues is very promising.

AC: Tristan, Francie (the other two co-directors of the CESAH) and I “experienced” these synergies when writing the CESAH’s scientific project. The result is not only coherent but also very inspiring. Examining both individual and collective research, we have found that the CEH and CEIAS could but nurture each other and give rise to promising axes of research. Besides, the work we’ve done together as directors so far also bears witness to the fruitful synergies between both ex-teams. For example, a 3-day conference planned in 2024 will be organized by members of both ex-teams (including ourselves). Our hope is that this will concretize the merger process and put the CESAH on the map internationally!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social Sciences Winter School in Karachi 2022

|

|

Cities, Urban Change and Heritage Management through Geotechnologies and Digital Humanities

|

|

A report by Michel Boivin and Rémy Delage

|

|

A Social Sciences Winter School (SSWS) was held in Karachi from November 21 to 26, 2022, in partnership with the CEIAS (CNRS-EHESS) and the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) of Karachi University. It took place on the City Campus of this institution, and benefited from other funding from several local institutional partners. The SSWS was organized by Michel Boivin (CNRS-CEIAS), Rémy Delage (CNRS-CEIAS) and Akbar Zaidi (IBA). It brought together 21 speakers (10 from Pakistan and 11 from France) and 45 participants (36 from Pakistan and 11 from abroad including 5 PhD students from France).

The issue of heritage in the social sciences was introduced in four plenary sessions and operationalized in three distinct methodological workshops:

(Download picture)

Group photo, IBA Main Campus, Karachi

https://winterspy.hypotheses.org/20221125_234033-2

The general idea of the SSWS is to develop a multi-disciplinary and intensive training course in the theories, methods and tools of social science research. The project also aims to strengthen regionalism and multidisciplinarity in the social sciences, and promotes the transfer of skills and the development of local skills. This first edition of the Winter School in Karachi enabled 45 participants from various academic, disciplinary and geographical backgrounds to be trained and supervised by some twenty French and Pakistani teacher-researchers in three multidisciplinary methodological workshops.

The theme chosen for this first edition in Karachi is fully in line with the intersection of the multidisciplinary fields of urban studies and heritage studies: Cities, urban change and heritage management through geotechnologies and digital humanities. In the context of this training course, we were more particularly interested in the relationship between heritage and local territory. Heritage was not considered in the strict sense of cultural heritage to be preserved but rather as a complex and multi-scalar process involving actors and institutions, as a component of the process of belonging and a structuring dimension of the territorialization process.

In addition to the theoretical and thematic introductory sessions, half a day was set aside for practicing fieldwork and the implementation of methodological protocols:

- Workshop 1: three groups devoted half a day to various practical exercises in the historical district of Kharadar which has particularities in terms of the juxtaposition of religious and architectural heritage: topographical inventories, sound surveys and short interviews.

-

Workshop 2: Private visit to the National Museum of Pakistan (Karachi) and practice photogrammetry in the gardens for the purpose of 3D modelling of historical monuments and sites.

-

Workshop 3: visit, presentation and handling of the archive collections located at the Sindh Archives in Clifton, more specifically specialized archives on the Karachi municipality and its markets during the colonial period.

A workshop session at IBA City Campus, Karachi

https://winterspy.hypotheses.org/img_1599-2

Several cultural activities were organized in conjunction with the training:

-

Frere Hall: Karachi, guided tour on Saturday 19 November 2022

-

Heritage Walk Karachi: Guided tour on Sunday 20 November 2022

-

Mohatta Palace: Karachi, guided tour on Thursday 24 November 2022

- Sindhi music concert: Winter School closing night on Friday 25 November at the Alliance Française de Karachi.

-

Makli-Thatta-Keenjhar Lake (Sindh): visit to the Makli Necropolis, one of the largest in the world, on Saturday 26 November 2022 and the Shah Jahan Mosque (17th century) in Thatta.

This Social Sciences Winter School project in Karachi is intended to be sustainable and therefore means to capitalize on the experience of the first edition, with the same university partner, IBA. The (provisional) theme of the 2023 edition will be focused on the study of the relationship between environment and climate risk vulnerabilities in South Asia.

For more information and to get all current information about the forthcoming editions, don’t hesitate to visit our website:

Winter School Karachi →

Thanks again to all the partners

|

|

|

FEDERALISM CONFERENCE

May 24, 2022, Campus Condorcet, EHESS

The First Event of the "Federalism Project: Theories and Practices"

|

|

Report by Laure Assayag-Gillot and Vishnu-Kumari Tandon

|

|

|

On May 24, 2022, an international conference on federalism was organized in Paris. This was the first event scheduled within the framework of the Federalism Project that was launched in 2021 by the two of us, Laure Assayag-Gillot (Raymond Aron Center for Sociology and Politics, CESPRA) and Vishnu-Kumari Tandon (then Center for Indian and South Asian Studies (CEIAS) and then Center for Himalayan Studies (CEH), both PhD students at the EHESS (School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences, Paris, France). Our keen interest in federalism brought us together as a team to launch this project. Its aim is to initiate fruitful institutional and scientific exchanges on the topic of federalism, while furthering scientific knowledge, setting up a network and creating opportunities for publications.

Federal issues and the reality of existing federal states cannot be clearly dissociated from each other. Thus, a comprehensive analysis of institutional philosophical roots can help us to further our understanding of federal institutions and to design appropriate analytical tools for investigating elements of multilevel governance systems. In the same vein, Laure and I planned the Federalism Conference as a way of exploring constitutive theories of federalism and of investigating federal practices based primarily on case studies from Asia. Through this conference, we aimed to renew the debate on federalism theory and practice, integrating various research strands (participatory democracy; comparative politics and constitutionalism).

Image 1: Flyer of the Federalsim Conference.

We chose Asia because, despite being the site with the most innovative and recent federal experiments (e.g. India, Nepal, Pakistan), Asia has remained one of the most neglected regions within the field. We sent out a call for papers in early January 2022 and were amazed by the thrilling response from senior and junior scholars worldwide. With the scientific committee's help, we selected the nine best papers for the four set panels. Papers from the fields of political science, law and philosophy were accepted for the conference to address questions about federalism, while bearing in mind the theoretical and empirical underpinnings.

The conference was organized in hybrid mode. Many scholars traveled from different parts of the world to attend the conference. On May 24, the conference began at 8.30am with an introductory speech delivered by Laure and myself, in which we explained the overall aim of the federalism project and the federalism conference. The first panel began with a talk entitled Centripetal Federalism in the Deeply Multilingual States by Professor Sean Mueller (University of Lausanne, Switzerland) and Professor Nenad Stojanović (University of Geneva, Switzerland). They explored dimensions of togetherness in deeply multilingual states by developing, measuring and testing the impact of centripetal federalism. The presentation demonstrated how the notion of shared rule contributes to cohesion where regional autonomy undermines togetherness.

Andreas Follesdal (University of Oslo, Norway) presented the second paper of the first panel. The paper was entitled Federalism — Philosophical Aspects. Professor Follesdal reminded us that philosophers once played a central role in the analysis and development of federalism. Therefore, their work should not be overlooked. The presentation offered a taxonomy of federalism and compelling reasons to opt for federalism, whether compared with secessions or compared with the choice of a unitary state.

Photo 1: Philippe Crignon (left) and Andreas Follesdal (right).

The second panel started after a short tea break. The first paper of this panel was entitled Federalism and Secessionism: Static and Dynamic Autonomy. It was presented by Professor André Lecours (University of Ottawa, Canada). He analyzed the stability/cohesion framework for federal and federated entities based on a case study of nationalist movements in Western Europe. He did this by underlining that the nature of autonomy is crucial to explaining distinct outcomes. He also elaborated on why static autonomy is more likely to stimulate secessionism than dynamic autonomy.

Photo 2: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine (left) and Krishna Hachhethu (right).

The following presentation, entitled Hybrid Federalism in Asia, was jointly presented by Professor Baogang He (Deakin University, Australia), Dr Laura Allison-Reumann (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) and Dr Michael Breen (University of Melbourne, Australia). Interestingly, the paper used biological processes of hybridity to develop these scholars’ approach to research and their hypotheses. They argued that hybrid federalism, with ethnic and territorial components, has a high probability of maintaining stability (India, Malaysia and Pakistan). By contrast, pure ethnic federalism can fail (as in Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Myanmar).

The third panel began after lunch. The first presentation was from Professor Arora (professor emeritus, Jawaharlal Nehru University). The presentation was entitled Continuity and Change in Indian Federalism: New paradigms of intergovernmental interaction (1991–2021). This paper explored the transformation of the Indian federal system with reference to the changes in the party system and the new dynamics of centralized federalism. He analyzed Indian federalism from 1991 to 2021 and linked it to the fundamental changes in the party system. He stressed that when a single dominant party comes into power, centralized features can become more prominent, impacting intergovernmental interaction provided by the Constitution. The first half part of the conference ended with Professor Arora’s presentation.

Professor Krishna Hachhethu (Tribhuvan University, Nepal) gave the second talk of the third panel. He argued that political parties are the powerhouse of a multiparty system. The optimum setup for power proliferation is where the parties in sub-national governments (at least in a few—if not in many and all—provinces) are not the same as those in the national government. He acknowledges that federalism in Nepal remains very central, restricting provincial autonomy.

Then, Dr Sai Oo (research coordinator and national representative of Myanmar’s Pyidaungsu Institute for Peace and Dialogue) presented a paper entitled Myanmar’s Federal Dream and its Dilemmas. He emphasized the fact that all federal agreements in Myanmar have so far only focused on the protection of ethnic minority groups instead of on proper provisions for power sharing between the states and the union. This has led to the failure of all federal attempts in the last seventy years. However, on the bright side, the community-based non-state institution in Myanmar that has prevailed for several decades, in the absence of any state government service, might offer a way to a federal democratic society.

The fourth panel began with a presentation entitled From the Separation of Powers to the Federative Republic: The Federalist’s Interpretation of The Spirit of the Laws by PhD student Hugo Toudic (Paris Sorbonne, France/University of Chicago, United States). He pursued a philosophical enquiry, albeit in a different context and timeframe. His transatlantic comparison explored the various ways in which the authors of the Federalist used Montesquieu’s ideas and concepts to advance the federalist cause in order to explain what strengthens the separation of powers and what the Founding Fathers and Montesquieu owe each other.

The second paper of this panel, and the last paper of the conference, was presented by scholar Ms Timmayo Thumra (School of Law and Government, Dublin City University, Ireland). In her paper India and Nagaland: Examining Federalism in the Context of an Evolving Ethnic-nationalist Fervor, she examined the asymmetrical federalism of India in relation to the Nagaland state. She demonstrates how the asymmetrical federalism of India (Art. 371) allows the Nagaland state to enjoy autonomy and privileges. However, at the same time, the central authority restricts the autonomy of political affairs and militarizes the Naga populace by means of the Indian Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), dated 1958, which cracks down on citizens and insurgents alike. Also, the special provision protecting customary laws has discredited Naga women’s political rights. The conference ended with messages of thanks and was followed by a cocktail party.

We are very grateful that the following renowned scholars agreed to act as discussant for the papers presented at the conference: Francesco Palermo (University of Verona, Italy), Philippe Crignon (University of Nantes, France), Bernard Fournier (Haute École de la Province de Liège, Belgium), Stéphanie Tawa Lama-Rewal (Center for South Asian Studies, CEIAS, EHESS, France), Loraine Kennedy (Center for South Asian Studies, CEIAS, CNRS-EHESS, France), Marie Lecomte-Tilouine (Laboratoire d'Anthropologie Sociale, CNRS-EHESS, France), David Dapice (Harvard Kennedy School, United States), Constantine Vassiliou (University of Houston, United States) and Philippe Ramirez (Center for Himalayan Studies, CNRS, France).

Photo 3: Laure Assayag-Gillot (left) Vishnu-Kumari Tandon ( right).

Similarly, our thanks go to the scientific committee members: Professor Cheryl Saunders (University of Melbourne), Professor Daniel Weinstock (McGill University), Professor Harihar Bhattacharyya (University of Burdwan), Professor Indira Rajaraman (National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi), Professor Kalypso Nicolaïdis (University of Oxford, European University Institute), Professor Min Reuchamps (UCLouvain), Professor Rekha Saxena (University of Delhi), Professor Sudha Pai (Jawaharlal Nehru University) and Dr Parul Bhandari (Center for Multilevel Federalism, Center for Social Sciences and Humanities-CSH). The committee’s advice provided added value to the conference’s scientific content.

Throughout the conference, two bachelor students, Rita Guerin (INALCO, Paris) and Bill Tsai (University of Illinois, Chicago), both with a great interest in the politics of Asia, provided logistical assistance. The conference would not have been possible without their help. We are equally grateful for the funding provided by the CEIAS, CEH and GIS-ASIE which allowed us to make the conference a success.

As a follow-up to the Federalism Conference, our next venture in the Federalism Project is to publish a book. Like the Federalism Conference, the book aims to bring together federal theories and practices from Asia. We would like to thank George Stairs (Forum of Federations) for advising us on the publication of the book. We have already contacted Emily Ross, senior editor, at Routledge. At the moment, we are in the process of sending a call for book chapters to scholars specialized in federalism. We aim to publish the book in Routledge’s Federalism Studies series. The details of the conference and the project are available at: https://federalism2022.sciencesconf.org

Openedition.org →

|

|

From the Field

|

|

On the Field of History.

|

|

Report by Raffaello De Leon-Jones Diani

|

|

Oftentimes, the poor historian that I am feels a pang of envy when listening to the wonderful tales that spill forth from the mouths of sociologists, anthropologist, sociolinguists and the like, who come back from their fieldwork enriched and enlivened by experiences the likes of which are often found in the pages of adventure novels. I have heard tales of prowling tigers, medusa-filled lakes, arid deserts. Many researchers recall beautiful fragrant dishes, harrowing journeys, hush-hush topics, and they all hint at an infinite number of stories still to come. Inevitably, there comes the time when I―perhaps too conspicuous by my silence―have to share in the tale-telling. Dread… my parched lips open and from my dry throat come the words: “Well, I can tell you about the British Library.” Those listening suddenly recall urgent appointments, and, within seconds, I am left alone to ponder: what is the nature of my fieldwork?

Uneventful it is, though not without wonder. Although my eyes have seen glorious sights both old and new, these―perhaps because of my poor eyesight―have often left me with only a fraction of the emotion that filled my heart when first I stepped into the grounds of the British Library. Walking briskly through the modern courtyard, I stepped forward with the confidence of a newborn toward the glass doors that would lead me into the inner sanctum. The continental European that I am, forever prone to all sorts of ID checks, bag checks and metal detector checks when it comes to such prestigious institutions, had already presented his bag; however, the guards, with the faintest of smiles, simply ushered me in. I stopped and asked if I could indeed step forth without having to state my paternal grandmother’s maiden name. Bemused, they nodded, and I―bewildered by such liberalism—made my way to the Reader Pass Application desk. I shall not tell you about the surprise that awaited me there too when it soon became obvious that the only prerequisite was valid ID and a home address. Nor will I tell about how helpful staff patiently answered my anxious questions and happily handed me centuries-old manuscripts. I still scarcely believe how simple it was.

And there it was: on my desk sat an ancient tome, a Book of War, generations old, penned by scribes of egregious talent, all for me, for me alone. I felt the pages under my fingers and breathed its fragrance that had journeyed so. In this book, where tales of yore had travelled from one language to the other, were left the impressions of countless hands, of countless voices and―I almost blushed—perhaps even the laughter of an Emperor, the Greatest of all. Any edition can reproduce the contents of a manuscript, but it is the manuscript itself that is the vector of our fancy. Though our research may not lead us to other lands or enable us to make new friends, those of us who deal with ancient words do indeed travel whilst immersed in times long gone. Within the reach of our hand is a thread that leads us into the past: not until I stepped through those doors had I realize that we had a field, that our research was very real and that it took very little to gain access to it.

This is what struck me most: that though I was reading these texts for academic purposes, it was the badge issued earlier―at no cost I might add―that granted me access to them. This badge could be issued to anyone, and anyone could read the books. I find solace in that.

So, until such time as I can tell you about other libraries…

Report by Raffaello De Leon-Jones Diani

|

|

|

First Step in the Field

|

|

Report by Saba Sindhri

|

|

My thesis is about a peripatetic group called the Samis, located in Sindh province in Pakistan. Compared with other groups such as pastoralists, non-pastoralists or sedentary people who have attracted the attention of numerous scholars including anthropologists and sociologists, the Sami people have rarely been the subject of academic studies. Locally known as sorcerer-beggars and spies, Sami people themselves claim to be beggars and to know how to tell people’s fortunes and to practice alchemy. To earn money, they wander from place to place between Sindh and Baluchistan provinces, and they also travel to Iran. When begging, they tell people’s fortunes using dice, called dharo, and perform alchemical activities to heal people. They also trade precious stones which they bring over from Iran and sell to people in Sindh and Baluchistan. As for their religion, they worship individual goddesses and follow Jafria tariqa, which is associated with Islam. No detailed survey of the Sami people has ever been carried out before, thus their settlement techniques, their beliefs and their professional activities remain largely unknown. I set out to review them in my thesis.

Photo 1: Sami fortune-telling dice.

The first time I went to Sami people’s settlement/houses, called pakha (singular: pakho), located in the village of Shahbandar in Thatta district in the south of Sindh province, was in January 2019. The purpose of my journey was to conduct a field survey about Sami people’s religious conversion (from Hinduism to Islam) in late 2017. In fact, the idea of studying this community has evolved from my initial doctoral project about the religious conversion of untouchable communities, officially known as scheduled castes in Pakistan. Indeed, I was drafting my doctoral project in October 2017 when I came across a news item in the Sindhi newspaper, Kawish, announcing that more than two hundred people from the Sami community in Shahbandar village had embraced Islam. An event to celebrate their conversion was organized by the owner of the land on which these Samis had settled. And pir Ghulam Muhammad Soho Qadri, an influential religious figure in the area, had been saying prayers for their conversion. I therefore had the idea of starting my fieldwork among this community and of exploring the reasons why such a large number of people from one community had decided to convert.

Photo 2: Sami houses (pakha) in the background.

Photo 2 bis: Sami houses (pakha) in the background detail.

I was taken there by a local journalist who had reported the news about their conversion and had been in contact with the head of the Samis in Shahbandar, Hameer Shaikh, who used to be called Hameer Sami before converting to Islam. The journalist had already told Hameer Shaikh about my visit so he was there waiting for us when we arrived. He welcomed us warmly and took us directly to the newly built mosque at the entrance to their village. At the time of my visit, building work hadn’t been completed. Hameer Shaikh told us: A religious scholar called Mullah has been appointed to teach Salat and the Islamic scripture of the Quran, and people have started praying there as well. After visiting the mosque, I asked Hameer Shaikh if he could take me to visit their pakha. He agreed and we set off. After about five minutes’ walk, Hameer Shaikh pointed to the houses surrounded by fields in which lucerne and brassica were growing. To get to the houses we crossed the fields. In comparison with the mosque that was solidly built, Sami houses were made of reeds and bamboo sticks covered with clay. There, I met Sami women who were busy doing household chores and quilt making.

Photo 3: Sami showing his knowledge about healing practices.

Photo 3 bis: Sami showing his knowledge about healing practices detail.

During the survey, Hameer Shaikh told me the reason for his converting to Islam. He explained: We were Samis, Sami beggars. We used to beg for a living but then we decided that, since we already live according to the Musalmani method, follow Safi tariqa, believe in everything and don’t build temples as Hindus do then, why do we live in the shadow of Hinduism. Thus, to escape this Hindu label, we became Muslims. Most people I met stressed how they had been impressed by the Islamic faith and their desire to be included among its believers. On hearing their answers, I soon realized that my set of questions was too direct for them to answer in total honesty. Indeed, the subject of religious conversion is a sensitive subject in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Also, it was the very first time we met. Nevertheless, this field visit prompted me to pursue various research threads for future work among these people. Hameer Shaikh’s explanation about Safi tariqa and the absence of religious spaces such as temples made me curious and got me interested in the Samis who had not converted. Therefore, during subsequent visits, I went to visit other Sami people in different villages, towns and districts of Sindh province. These visits broadened my understanding of Sami people but also considerably shifted my focus from religious conversion to many questions about their migration routes between Pakistan and Iran, their customs, beliefs and activities as fortune tellers, their knack for getting money from clients, women’s quilt-making activities of and, more importantly, their worship of different goddesses. I address these questions in my thesis.

|

|

|

Legally Included but Socially Excluded

|

|

Report by Vishnu Tandon

|

|

This account focuses on the political contributions and compromises of a female Dalit who is elected as representative of Nepal’s Dhanushadham municipality. This is one of the municipalities I’m studying for my doctoral thesis. My research examines municipal planning in Nepal, an annual process organized by local elected representatives to formulate local plans for building local infrastructures and for initiating social development policies based on proposals collected among ordinary citizens in settlements or tole. The newly introduced federalism (2015) has brought in legal arrangements that allow the 753 newly formed local government units (rural and urban municipalities) to receive a massive budget transfer from provincial and central governments.[1] These budget transfers have sparked an interest in standing for elected office as representatives because the latter play an important role in allocating municipal budgets to small-scale projects by organizing settlement assemblies, tole bhelas, during the planning process. During my fieldwork in 2021, I met several elected representatives in Dhanushadham municipality and its sub-municipal units, the wards.

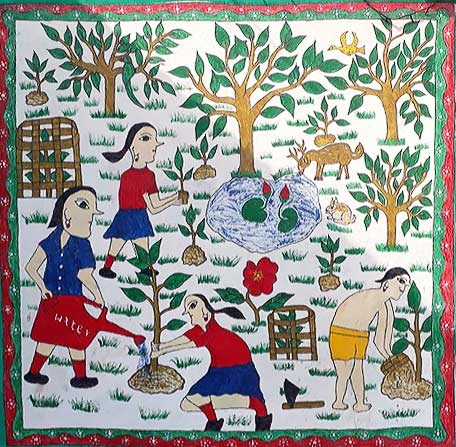

Photo 1: Mithila art drawn by a student.

Photo 1 bis: Mithila art drawn by a student detail.

For the first few days of my visit, I was able to meet only male elected representatives, as they were the only ones available in the ward offices. I wanted to meet some female elected representatives, so some of them suggested I meet Anita.[2] The chairperson of the ward I was visiting said, “you should meet Anita, who was elected for Dalit reservation quota from our ward. She knows everything.” I was pleasantly surprised to see a Dalit woman appreciated by a high-caste elected representative.

I met Anita the very same day. She wanted to do something for her community; that’s why she ran for the ward-member position. Before being elected, she was engaged in many voluntareer activities with different community development organizations that worked toward Dalit upliftment. For instance, a few years ago, she volunteered for a project run by a local NGO that built an after-school learning center (tuition center). At this center, Dalit children from her neighborhood attend additional classes that help them with their homework because most of these children’s parents are illiterate and can’t help them. The children also learn Mithila art, a type of art practiced in the Maithili-speaking region of Nepal and India. Anita showed me some walls painted by a Dalit student (Photo 1). She herself had never had the opportunity of attending school but had participated in many adult literacy programs organized by local NGOs so that she could learn to read and write. Anita believes that a good education for children can improve the condition of Dalits in the long run.

After being elected as representative in 2017, Anita played a vital role in organizing tole bhelas. She would collect project proposals within her neighborhood, then forward them to the ward assembly that establishes a shortlist of the projects. When I asked her how she learned to collect local proposals, she said, “it is not difficult to identify the needs of your people.” As ward member, Anita enjoyed what she was doing for her community. She wanted to do more. She expressed her desire to run again in the 2022 election, but this time for the position of ward chairperson instead of ward member. Following the federal restructuring of Nepal, every ward has a committee of five elected representatives, including a chairperson and four members. The position of ward chairperson carries the most power. She reasoned that, as there is a significant population of Dalits in her ward, if a Dalit runs for election, they can win. I was amazed by her confidence.

I returned to Dhanushadham again in early June 2022, right after the local election which had taken place in May 2022. I saw her name in the list of elected representatives, but she had again been elected under the Dalit member quota. I wanted to know what had made her change her mind. I met her the following day and congratulated her on her election. Then I asked her why she hadn’t run for chairperson. She replied that senior party leaders had suggested that Dalit seats are reserved for the member position only, not for chairperson, so she couldn’t run for that position. And she didn’t get a ticket from her political party to run for chairperson. She regarded it as law, so she had to accept it.

Photo 2: Tole bhela of year 2022, in Anita’s tole: she is the only electedrepresentative who does not get the chair

The law that has been in place since 2017, the Local Government Operation Act-2017, states that the political party should nominate at least one Dalit woman for the position of ward-member. However, it does not forbid any party from appointing women or Dalits to the position of ward chairperson. The aim of providing reservation to Dalits was to ensure at least minimum representation of Dalits in local politics. But the “minimum representation” has been interpreted as the “maximum limit."

Anita no longer has her eye on the ward chairperson’s position because she believes that she can only run for the seats reserved for her. However, she’s not disappointed and continues to work for the community as ward member and to organize the tole bhela. In 2022, I was able to attend the tole bhela in her settlement, as well as to observe the other ward representatives there. Anita gathered together people for discussions and then noted down the demands of the population. There were three other elected representatives at the tole bhela. It is worth noting that during the meeting, every ward representative except for Anita was offered a chair to sit on. She stood the whole time (Photo 2). Offering a chair is a sign of respect in Nepali society. Though this story is just about one Dalit woman, it shows that, despite Nepal's reformed laws and reservations for Dalits, social inequalities are still rife in the country.

[1] The newly introduced federalism (2015) brings legal arrangements that allow the newly formed 753 local government units to receive about 32% of the budget (20% from the central government and 12% from the provinces) to be utilized through a participatory planning process.

[2] Name has been changed to maintain confidentiality.

|

|

|

Pyangaon Revisited: Tradition and Continuity

|

|

Report by Gérard Toffin

|

The anthropology of change and modernity is a multifaceted issue. How has the small single-subcaste Newar[1] agricultural village that I studied in the early 1970s been affected by the major transformations that Nepal has endured over the last fifty years? In November 2022, I made several visits to the place where I conducted my initial fieldwork which is located about 17 km south of Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. A number of young boys immediately welcomed me, repeating that they were the sons of so-and-so with whom I was on familiar terms. “We need your help to preserve our original culture,” they all insisted[2]. It was not the first time I had been back to this locality; yet such visits rapidly became the main focus of my recent trip to Nepal. As the two photos reproduced here show, Pyangaon (in Nepāl bhāṣā or Newari: Svãgu), populated by a particular agricultural subcaste, has changed considerably. With regards housing, bricks have often been replaced by cement, and pitched roofs by flat terraces. The ceilings are higher and the carved wooden windows have disappeared. In addition, new houses have been built around the pond at the entrance to the village and some of them are rented out to Tamang and Hindu Bahun-Chetri groups, i.e. outsiders. The village appears to be cleaner and less insalubrious than fifty years ago. Buffalo husbandry, so essential in the past for the sale of milk to faraway places, has been abandoned. However, the only street in the locality, still flanked on both sides by high wooden stakes to dry maize and by two compact rows of terrace houses, is still the same. A new arched concrete gate at the entrance to the village reinforces the demarcation between Pyangaon and the outside, and sustains the sensation that one is entering a reclusive, secluded, community.

The standard of living and people’s everyday clothes have considerably improved, as has their lifestyle. In most houses, there are TVs and modern furniture (in 1970, there was no electricity). The village has entered the digital world of the World Wide Web: young people have a mobile phone, an Internet connection and surf Facebook and Tik-Tok. Furthermore, Pyangaon/Svãgu, which has never been a self-sufficient locality, is increasingly dependent today on a market economy. The use of old horizontal weaving looms, where the woman operating it sits on the floor, has practically been abandoned. Ready-made garments are now worn and are bought on the market. Farming (irrigated rice and non-irrigated crops such as maize, mustard and wheat) still remains one of the inhabitants' main occupations, but often only on a part-time basis. Thanks to schooling, more and more young educated boys (and a few girls) work as clerks and accountants in neighboring towns. It takes them only 30–45 minutes in the morning to go to work by motorbike and the same amount of time in the evening to return to Pyangaon. Other men are employed here and there in the building sector. Some fields, especially those situated furthest away from the village, have been sold at a very high price. What is more, young people are trying to revive the craft of making bamboo containers, pyāṅg (or dyāṃcā, hāpā) (hence the Nepali name for the village), once used to measure grain and to store varieties of spices.

The population has more than doubled (about 1,400 persons at present, instead of 550 in 1970, yet the village has retained its unique identity. Its rural character still differs markedly from the nearby cities of Kathmandu and Lalitpur (Patan) and its specific Newari dialect, bhāṣika, is still spoken in the locality. From a sociological viewpoint, the division of the village into two factions subsequent to a debatable case of intercaste marriage with an outsider in the 1940s is no longer discernible. In fact, nowadays, intercaste marriage with girls from outside the locality is increasingly challenging the traditional mode of marrying endogamously. “Now, everyone marries girls from outside,” says teenager Sumina Maharajan. The gap between the younger (kvakāli) and older (thakāli, or thakāri in the local language) generation is therefore widening. However, sociologically, the holistic features of Pyangaon still prevail. Members of the community (Svãgumis, “the people of Svãgu,” in the local language) are still encapsulated within an all-encompassing social order. They have to accept binding communal rules and are submitted to a strict organization of labor, an annual calendar of festivals and ceremonies, as well as to a large number of obligations towards their relatives. These constraints do not basically differ from what I observed fifty years ago. If marriage is contracted with somebody from outside the village, even with a girl of higher caste, men retain their membership within the local group, but their sons are excluded from the main socioreligious events. By and large, patrilineal kinship remains one of the roots of local society. Nonetheless, young women have now formed voluntary groups, mahilā samūha, in order to be more independent, to manage their own savings, or to heat the inner bark of bamboo in the fire for making pyāṅg containers. On the whole, they try to impose their own vision of the future—an outcome of the recent mahilā feminist movement in the country. In matters of political orientations, wood sculptor Narendra Maharjan, one of my old friends from the village, who recently converted to Christianity under the influence of a local Jehovah’s Witness church, informed me that in November 2022, during the general elections, Svãgumis cast votes in favor of a wide range of political parties (not just a single one): Communist, Congress, and others. “Options even vary within a family,” Narendra told me.

Religion, which is basically ritualistic among Newar farmers or former farmers, is still a pillar of society. A number of rituals and ceremonial observances, mostly of a Hindu character, structure social life. Pyangaon, for instance, still celebrates a major eleven-day-long joint festival (mū yāḥ) at the end of the rainy season; the five guthi (locally known as gvahã), socio-religious groups rooted in kinship units, take part in it. The old theatrical play kuṃ pyākhã (or rājā-rāni nāc) staged during the festival has been revived with a modern twist. Interestingly, local people now compete with ethnographers in photographing and filming ceremonial events with their mobile phones. Above is a reproduction of a photograph illustrating the khaḍga jātrā (in the local dialect: kharyacā yāḥ) procession during vijayā daśamī day, which was taken in October 2021 by Mahila Maharjan, now a retired schoolteacher. Another photograph (below) that I took shows three Navadurgā masked dancers (from left to right: Byāṃghīṇī, Mahālakṣmī and Siṃghīṃnī) from Theco, a nearby Newar village, resting on a bench during the performance of the sacred dance which, once every twelve years (this event took place in 2022), takes on a special dimension, with more deities participating in the dances. On that occasion, most of the inhabitants of Pyangaon have to offer flowers, rice, and money to the dancers who embody the divinities. Thanks to my good relations with one of the persons in charge of the dance, Prasant Mallakar, I was able to visit the inside of the new small temple dedicated to these nine Durgās—a temple that was recently rebuilt after being destroyed during the 2015 earthquake. For the rest of the year, the masks of the deities are housed here. Outside, the remains of the large hut (balcā) that was used for celebrating important rituals every twelve years were still visible.

Two conclusions can be drawn from this summary report. 1. Altogether, three forms of attachment, both secular and religious, continue to prevail in Pyangaon: to basic local patrilineal kinship units, to the small single-subcaste village and, lastly, to the Newar ethnic group. This triadic configuration roughly defines the Svãgumi system of belonging, both past and present. 2. The report also shows that even if macro political, demographic and economic data on transformations are of major import, the findings of local inside ethnological micro-studies are also crucial and sometimes provide a more comprehensive viewpoint of the sociocultural facts.

|

|

Note that “Newar” designates a highly Indianized ethnic group speaking a Tibeto-Burmese language and claiming janjāti indigenous status, though it is divided into more than 30 main castes.

I would particularly like to thank Shova Laxmi Shakya, Sight Sing Maharjan, and Sumina Maharjan for their help during my fieldwork (Pyangaon).

|

|

|

|

|

Daniela Berti

We’d like to congratulate Daniela Berti for attaining the rank of Senior Research Fellow. For the past several years, Daniela has been working on Indian court systems and she is now heading us the ANR program Ruling on Nature: Animals and the Environment before the Court.

Anne Castaing

The CESAH is happy to congratulate Anne Castaing for passing her Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches in June 2023, under the title of “Literary practices of History: South Asian writing, 20th-21st Centuries.” It notably included a monograph, “Paradoxal Testimonies: Writing the 1947 Partition.”

Anne Castaing works on modern South Asian literatures and is particularly focused on the literary representation of history. Among other publications, she has edited and co-edited 9 volumes, including Performance et littérature en Asie du Sud. Réciter, interpréter, jouer (with Ingrid Le Gargasson, 2022), Genre et nations partitionnées (with Benjamin Joinau, 2020) and Raconter la Partition de l'Inde (2019).

|

|

New PhDs

The CESAH would like to congratulate the PhD students who have defended since the last issue. Bravo to all!

|

Aneela Durrani

The Sufi Path of Amity: A Case Study of the Azeemiya Sufi Order in Pakistan and Beyond in the Contemporary World

This research focuses on a Sufi tariqa recently created in Pakistan: the Azeemiya. It was founded by Muhammad Azeem Barkiya, better known as Qalandar Baba Aulia (1898-1979), with headquarters located in a compound where his tomb was built, in Karachi. Qalandar Baba Auliya was himself the follower of Baba Tajuddin (1861-1925), a Naqshbandi master from Nagpur, in India. Qalandar Baba Auliya wrote numerous Sufi treatises in Urdu, in which he developed his own brand of Sufi thought, claiming to be the heir of many different tariqa, such as the Qadiriya, the Chishtiya, the Sohrawardiya, the Qalandariya, and so on. Qalandar Baba Auliya also wanted his tariqa to be “modern” by giving it a large international audience, and allowing people of different religious persuasions to be granted initiation (baya). In this research, the main hypothesis is that instead of coining it as a “neo Sufi” tariqa, it is more relevant to study the Azeemiya by locating it in the context of “new religious movements,” a concept mostly built and developed in the field of the sociology of religions. To address the issue, the thesis is divided into three main parts: the emerging tariqa in the modern world; the organization in Pakistan and abroad; metaphysical and mystical thought in the Azeemiya writings.

José Egas

Challenges of a Multiethnic Territory: Conservation, Development and Politics in the Mountains of North Kerala, India

This thesis explores the relationships between social groups that are defined differently in accordance with their ethnicity and the state in Wayanad, a hilly district of the Western Ghats in northern Kerala, India. Focusing on Adivasi communities, the term used for indigenous peoples in India, the analysis looks at settlement dynamics and social cleavages in pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial times. In a first stage, the thesis provides an historiographic retrospective showing the models of political administration that governed this territory during the pre-colonial and colonial phases. In a second stage, the thesis analyzes the conditions of the Adivasi communities vis-à-vis other populations and forms of governance since the emergence of the postcolonial state. Land tenure systems in Kerala have benefited from redistribution processes through state reforms, which have democratized access for landless peasants. However, Adivasi communities have been excluded from these redistributive processes and have been exposed to processes of land alienation by different actors. The state has been unable to provide alternatives to guarantee access to this resource. Moreover, access to forest areas has been restricted due to the application of rigid environmental governance that rejects any anthropogenic activity in these areas. Considering that the Adivasis depend on forests for their survival, their participation in forest management, resource use and benefit sharing has been marginal. While the state has put in place a tribal development agenda to provide for the welfare of Adivasi communities and improve their living conditions, the programs included in this agenda have generally responded to the institutional demands of the state rather than the needs of the communities themselves. Various processes of intermediation between the communities and the state have been established to carry out the tribal development agenda; in these processes the Adivasis themselves have been actors in this intermediation, having limited levels of discretion to decide on the direction of the agenda. Faced with the situation of marginalization to which the Adivasi communities are exposed, they have exercised political responses of different kinds, among which protest politics and parliamentary politics stand out. Different results have emerged from these forays into politics, sometimes achieving positive attention to their demands and at other times resulting in nothing. Through a critical analysis of all these elements, the thesis seeks to shed light on the position of Adivasi communities in contemporary India.

Lou Kermarrec

The Garden, the Island and the Myth: Ethnography of Indianness in Guadeloupe and of a Circulation of Plants and Knowledge (West Indies, Mascarenes)

The question of knowledge related to plants, the environment and landscape has not been explored in the works about the migration of Indian indentured laborers (1834-1917) to the Creole-speaking islands of the West Indies and the Mascarenes. Similarly, the interdependence between plants, gods, myths and Hindu cults is not considered in works on the form of Hinduism practiced today on these islands. Starting from the case of Guadeloupe, I propose an ethnobotanical analysis of the modalities of the transmission of plants and their uses in families of Indian origin since the times of indenture, and a study on how these plants have spread throughout the landscape of the archipelago, over the longue durée. Using ethnographic, botanical and historical sources, I formulate hypotheses about the introduction of plants by Indian indentured laborers in Guadeloupe (19th century) and by their descendants (20th-21st centuries). When the relationship to the garden and the botanical landscape is inserted into an extended chronology, it allows us to question and contextualize the existence of Indian knowledge in the Creole garden, and an "Indianness" present in Guadeloupe. Plants structure Hindu rituals and allow interaction with the gods. In exile, myths, orally transmitted stories about the gods and the world, become knowledge. The practice of Hindu cults is approached from the angle of insularity and the link between the symbolism of plants and the notion of the sacred is based on a comparison between Guadeloupe on one hand, La Réunion and Mauritius on the other. Current exchanges between the Hindus of Guadeloupe, India, the countries of the southern Caribbean and the Mascarene Islands open new pathways of knowledge on plants and their uses. These exchanges have facilitated the introduction of numerous plant species that gradually spread in the gardens, in the context of a contact between "creole" Hindu practices and the circulation of more globalized Brahmanical knowledge. The spread of plants and the transmission of knowledge, at different times, between India and the islands of the West Indies and the Mascarenes, shape a particular relationship to the garden, seen as a place of intimacy and deployment of a singular belonging to the world. The present thesis is an attempt to illustrate the process of creolization, starting from gardens and Hindu places of worship, under a particular variable: that of temporality.

Nicolas Mauviel

“Engineering or Medicine. Nothing less”: The Social Construction of Educational Trajectories and Professional Aspirations of Kerala Students (India)

In 2001, the Kerala government’s approval to set up a significant number of self-financing colleges, especially professional ones, led to the mushrooming of privately-controlled higher education institutions. Engineering and Medical education, embodying ideas of success and prestige, started attracting a larger number of aspirants, which consequently resulted in freeing space within the traditional disciplines offered in the humanities, commerce and sciences. Although expansion of the university offer did increase the number of graduates in the population, opportunities for accessing the most coveted areas of study and the best institutions seem to be very unevenly distributed amongst the various social groups. In our research, we intend to shed some light on these inequalities by looking into the effects of reservation policies’ modes of application in the privately dominating and community-controlled higher educational institutions as well as into the educational strategies of students and their families. Lastly, we examine the conversion of university degrees into professional careers and the differentiated outcome and optimization of academic titles. To this end, the consideration of caste and class will be brought up and the role of capitals deriving from such groups will be investigated. In this effort, we intend our work to join in the debates over the weight of caste and class on social reproduction which appear to be more and more mediated by educational trajectories.

Mobility fellowship recipient

Thibault Lukacs

Thibault Lukacs was chosen to spend a semester at the University of Columbia as part of the EHESS bilateral international mobility agreement. He has been invited by professor Naor H. Ben-Yehoyada to be a PhD scholar at the Graduate School of Arts and Science, where he will be working at the South Asia Center as well as in the anthropology department.

A funded PhD student in anthropology at the EHESS, he has, for the past two years been working under the supervision of Aminah Mohammad-Arif, with David Picherit as co-supervisor, conducting ethnographic research on a mining basin in North India. He practices participant observation among the various actors of the extractivist economy: State mining company, informal mine workers, private companies and politicians. His work aims to advance knowledge of the socio-political phenomena that have been modifying the nature of relations between the business sphere, politicians and the various population groups since the 1980s. He is particularly attentive to certain contemporary forms of notabilization of political and financial elites associated with extractivist groups, as well as to processes of vernacularization of democracy.

|

|

|

|

|

Statutory Members

Margherita Trento

Margherita was elected associate professor at the EHESS. She is a historian of early modern South India and works at the crossroads between social history and the history of knowledge, literature and religions. Taking Tamil Shaivism and Tamil Christianity as the main focus, her research explores issues of translation, devotion, circulation, and the constitution of Tamil country as a region, as well as in relation to the Indian Ocean Space. Her first book (Writing Tamil Catholicism, Brill, 2022) offers an analysis of the process of localization of Catholicism in Tamil country in the 18th century, between missionary expansion and local devotion.

Fabien Provost

Fabien Provost was elected as a CNRS researcher affiliated with the CESAH. Initially trained as an engineer, Fabien Provost subsequently turned to social anthropology at the Université de Provence (MA, 2009–2011), then at the Laboratoire d’ethnologie et de sociologie comparative (Université Paris Nanterre, PhD, 2012–2019).

As a social anthropologist, his research lies at the crossroads between medicine and the law. In all, he has spent 12 months carrying out an ethnographic investigation in three North-Indian morgues. This fieldwork is the basis of his PhD dissertation in which he explores various aspects of forensic medicine practice. The results have been published in several peer-reviewed journals and edited works. His conceptual interests include the pragmatics of medical language, the production of knowledge about the body, and the articulation of the biological and the social in anthropological theory.

Associate Members

Naveen Kanalu

Naveen Kanalu is associate professor (maître de conférences) at the EHESS and holds the chair “The Institutional History of the Mughal Empire: Law, Power and Political Economy in South Asia (17th–18th centuries);” He received a PhD in History from the University of California, Los Angeles, and is currently working on a monograph titled, An Empire of Law: Hanafism and Islamic Statecraft in Mughal India. The book project examines the legal, political and economic history of the Mughal Empire during its phase of imperial centralization in the second half of the seventeenth century. His articles on Hanafi jurisprudence in Indo-Islamic polities, British colonial interpretations of Islamic law, and European representations of Mughal rule have appeared in journals and edited volumes. More broadly, his interests lie in Islamic documentary forms and chancery practices, Persianate culture in vernacular sociolinguistic contexts, and Arabic manuscript culture and Arabo-Islamic intellectual history in precolonial South Asia.

Paul Rollier

Paul Rollier is an anthropologist and CNRS researcher at the CéSor (Centre d’études en siences sociales du religieux). His research focuses on the anthropology of religion (Islam and Christianity) and on the cultural logics of justice, of what is licit and of political representation in South Asian Muslim societies. Since 2008, his work has been based on the numerous periods of fieldwork he has carried out in working-class neighborhoods in Pakistan’s Punjab province. He has co-authored Mafia Raj: The Rule of Bosses in South Asia (Stanford University Press, 2018) and co-edited Outrage: the rise of religious offence in contemporary South Asia (University College London Press, 2019). His current research interests include the issue of religious offence and Muslim-Christian relations in Pakistan.

Associate Early-career Researcher

Asad ur Rehman

His research focus is on understanding the contemporary social transformations in Pakistan’s Punjab province and their implications for the politics of the Pakistani federation, questions of inclusive citizenship, ethnic justice and representative claims. He teaches courses in South Asian history and politics, political sociology and advanced political theory. His book, Politics of Socio-Spatial Transformation in Pakistan: Leaders and Constituents in Punjab is soon to be published by Routledge International. He is also contributing a chapter for an edited volume on Thinking Peace from below: Liberatory Visions of the Oppressed which will be published next year by Springer.

On 26–27 October 2022, he organized a two-day international conference entitled “Whither Politics and Policy in South Asia: Developing a Comparative Regional Perspective.” He set up a working group as a spin-off from the conference and the group is in the process of developing a proposal for an edited volume with the working title Politics and Policy in South Asia: A Critical Perspective from the Peripheries.

Postdoctoral Scholars

Girija Joshi

Girija Joshi is a historian and works on northwest India. Her doctoral dissertation (Leiden University, 2021) focused on the evolving intersections between kinship, service and subsistence in late-eighteenth and nineteenth-century Panjab. One of the central themes of this project was the household as a vehicle for resource management and a site for creating a community. Using a combination of English, Persian and Urdu sources, her thesis tracked the changes to the household-centric rural economy of southern Panjab over the late-Mughal and colonial periods. Joshi’s postdoctoral project, funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), likewise explores the subject of community in northern India, but through the prism of Persianate historiography. Drawing on a corpus of sources written in various northern Indian courts, it explores how history was conceived of over this period, and the related ideas about community and governance.

Sarah Melsens

Sarah Melsens has joined us as a Marie Curie fellowship recipient. She is trained as an architect and has a PhD in the history of architecture from the University of Antwerp. After working on professional architects in Pune, she is now broadening her analysis to construction workers in the late modern period (19th and 20th centuries) in the same city and on the basis of both oral sources and photographic archives.

New PhD Student

Pierre Pfister

Pierre Pfister has joined us as a PhD student. He will be working on a project entitled “Adventures and Power Struggles in the Unamorous Indies: The Crisis of the Mughal Empire and the fortune of Sombre or Samru, Nabab of Sardhana (18th Century).”

Administrative Staff

Christopher Bermude

Christopher Bermude has joined us as administrative and financial assistant manager.

Wahid Mendil

Wahid Mendil has once again joined us as communications officer.

DHARMA Team Members

Hinda Khassouani

Hinda Khassouani is the new DHARMA European Project Manager and is taking on the management, administration, communication and dissemination of the project, via the “hypotheses” blog in particular (https://dharma.hypotheses.org).

Michaël Meyer

Michaël Meyer is the new DHARMA XML-data Manager. Among other things, he will set up the project database (online editions of epigraphic texts and manuscripts). Michaël is replacing Axelle Janiak, who is leaving us after four years of dedicated service.

Amandine Wattelier-Bricout

Amandine Wattelier-Bricout is joining the DHARMA team as a research fellow with a project on formulaic stanzas on gifts, which appear in particular at the end of inscriptions in South Asia.

|

|

The CESAH would like to wish a fond farewell to two colleagues we had the pleasure of having with us during the 2022-2023 academic year.

|

Visiting Scholar

Rinchen Dorje

A historian of religions by training (PhD University of Virginia, 2018), Rinchen Dorje teaches at the Centre for Studies of Ethnic Groups in Northwest China, College of History and Culture, Lanzhou University, China. He came over to France in October 2022 as visiting scholar at the Centre for Himalayan Studies and is now pursuing his activities within CESAH until July 2023. A specialist of the history of monastic institutions and lineages in Amdo, he also has a strong interest in contemporary religious developments in Amdo and socio-anthropological approaches to religion and ritual, which is the main reason for his visit to the CNRS.

Postdoctoral Scholar

Pia Bailleul

Pia Bailleul defended her doctoral thesis in anthropology in 2022 and joined the CESAH on a postdoctoral contract within the ANR project Rulnat (Ruling on nature: animals and the environment before the Court) run by Daniela Berti. Her research focuses on mining laws and technical mechanisms for the regulation of rare earth resources in Greenland where she has been conducting research since 2016. More generally speaking, Pia Bailleul has a keen interest in the forms the development of the mining sector has taken in this country and its impact on the territory from a legal anthropology-cum-ethnography of mining perspective.

|

|

|

|

|

Publications

|

Authored books

|

|

|

Ithurbide, Christine |

|

2022. Mumbai Hors-Cadre, une géographie de l’art contemporain en Inde. Lyon : Editions ENS.

|

|

|

|

Tignol, Eve |

|

2023. Grief and the Shaping of Muslim Communities in North India, 1857–1940s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

|

|

|

Weber, Jacques |

|

2023. Histoire de la civilisation indienne. Vol. 1, L'Inde ancienne et médiévale. De la civilisation de l'Indus-Sarasvati aux invasions musulmanes. Paris: Les Indes savantes.

|

|

|

Edited books

|

|

|

Castaing, Anne, and Ingrid Le Gargasson, eds.

|

|

2022. Performance et littérature en Asie du Sud. Réciter, interpréter, jouer. Aix: Presses Universitaires de Provence.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chicharro, Gladys, Stéphane Gros, Adeline Herrou, and Aurélie Névot, eds.

|

|

2022. Le Féminin et le religieux (The Feminine and the Religious). Paris: L'Asiathèque.

|

|

|

|

|

Jacquesson, François,

and Vincent Durand-Dastès, eds.

|

|

2022. Narrativité. Comment les images racontent des histoires. Paris: Presses de l'Inalco.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sood, Ashima and Loraine Kennedy, eds.

|

|

2023. India's Greenfield Urban Future: The Politics of Land, Planning and Infrastructure. Hyderabad: Orient BlackSwan.

|

|

|

|

|

Edited journal issues

|

|

|

Aubourg, Valérie and Mathieu Claveyrolas, eds. |

|

2022. L’Ethnographie du religieux dans les mondes créoles. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 197. |

|

|

|

Guillaume-Pey, Cécile, Leila Baracchini, Véronique Dassié, and Guy Kayser, eds. |

|

2021. Rencontres ethno-artistiques. ethnographiques.org 42. ethnographiques.org - Revue en ligne de sciences humaines et sociales |

|

|

|

|

|

Louis, Marieke, Jules Naudet, and Nicolas Pantin |

|

2022. “2022, l’énergie du politique.” La Vie des idées, February 1. |

|

|

|

|

Book chapters

|

|

| Bouillier, Veronique |

|

2022. “Current Research on Nath Yogis: Further Directions.” Pp. 31-54 in The Power of the Nath Yogis: Yogic Charisma, Political Influence and Social Authority edited by D. Bevilacqua and E. Stuparich. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

| Colas, Gérard |

|

2022. “Chapter 12. History of Vaiṣṇava Traditions: An Esquisse.” Pp. 209–44 in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. 2nd ed., edited by G. Flood. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [revised version]

|

|

|

|

|

| Colas, Gérard |

|

2023. "Palm-leaf Manuscript Libraries in Southern India Around the Thirteenth Century: The Sarasvatī Library in Chidambaram." Pp. 135-57 in Libraries in the Manuscript Age, edited by N. de Castilla, F. Déroche, and M. Friedrich. Berlin: De Gruyter.

|

|

|

|

|

| Colas, Gérard |

|

2023. “The Supreme Being: A Person?” Pp. 301–17 in Religious Transcendence Beyond Monism and Theism, Between Personality and Impersonality, edited by B. Nitsche and M. Schmücker. Berlin: De Gruyter.

|

|

|

|

|

| Colas, Gérard |

|

2023. “Une source de l'école védantique vaikhānasa. Le Lakṣmīviśiṣṭādvaitabhāṣya dans son contexte.” Pp. 159–88 in Mélanges à la mémoire de Pandit N.R. Bhatt/ Studies in Memory of Pandit N.R. Bhatt, edited by P.-S. Filliozat, D. Goodall, and P. Pasedach. Pondicherry: Institut français de Pondichéry/École française d'Extrême-Orient.

|

|

|

|

|

| Dupont, Véronique, and M. M. Shankare Gowda |

|